“The future engineer is a woman”

In its report last autumn, the German Economic Institute reported that only 32.5% of the people currently studying STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) subjects in Germany, were women. Further, women only make up 15,5% of people employed in STEM related jobs. Both these figures are slightly higher than the measurements from previous years. But considering that the male to female gender ratio in Germany is relatively even, these percentages are still very low. Why then, are women so underrepresented in STEM subjects and jobs?

We desperately need people who are trained and willing to work in STEM. The STEM report of the German Economic Institute estimates that there already is a shortage of about 280.000 people in STEM jobs, which will increase by about 27.000 annually in the next five years. The challenges we are facing as a country, requires people who are scientists, engineers, and researchers. To digitalise and modernise our economy, society, and infrastructure. And to shape and inform our responses to climate change. We need people who can innovate and futureproof our country for the coming years, and people who are trained and working in STEM subjects are a big part of that.

Why are female perspectives so essential?

Its not only people that we need. Its women specifically. A common example that is given to show why we need women in research, is that safety features such as airbags are not necessarily configured to the on average lower heights and weight of women. The male body is taken as the default. This is even more critical when it comes to medical research.

Women are underrepresented in clinical trials, often left out over concerns about how pregnancy or menstruation cycles might affect the results. As a consequence we have less data on how the technologies, treatments or medications being tested will affect pregnant or menstruating people. This means that some medications are less effective for women, or cause harmful sideeffects. This disparity does not stop at product development. Certain conditions or diseases may present differently in women – for example, a woman experiencing a heart attack might present symptoms different from those taught in a textbook. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrine disorder that affects women of reproductive age and is almost criminally underdiagnosed and -researched. It can be painful and traumatic, affect quality of life as well as reproductive and mental health. And yet, as of 2022 there is no cure for it.

Clearly, we need more women in research – medical and otherwise – to ensure that future innovations accomodate, or at least do not actively harm women and their bodies.

What is keeping women out of STEM ?

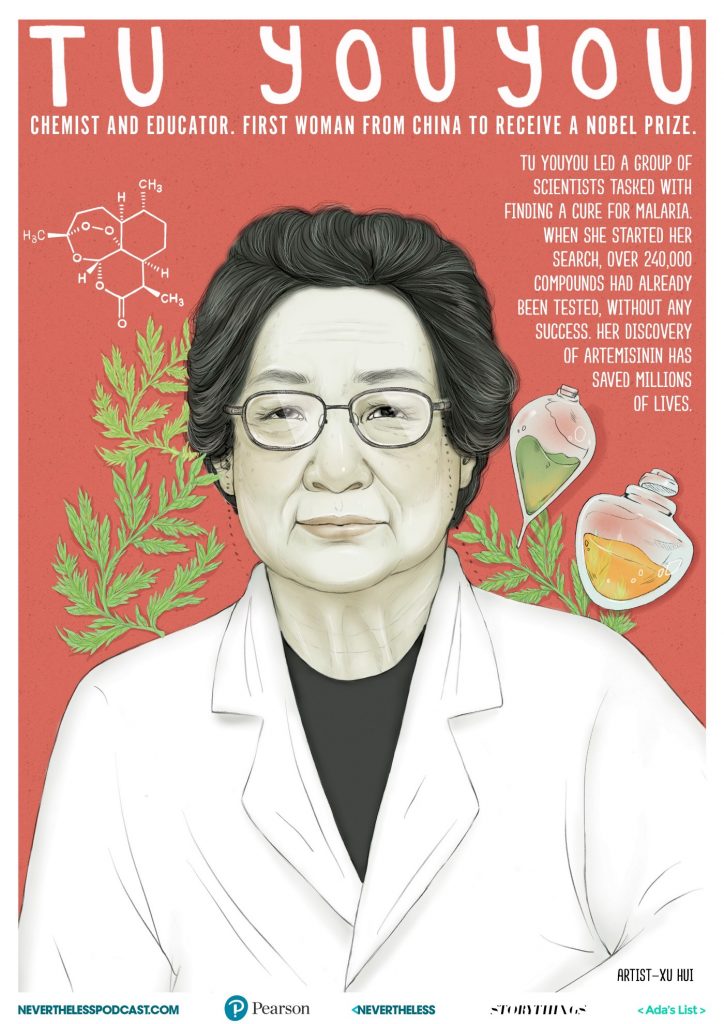

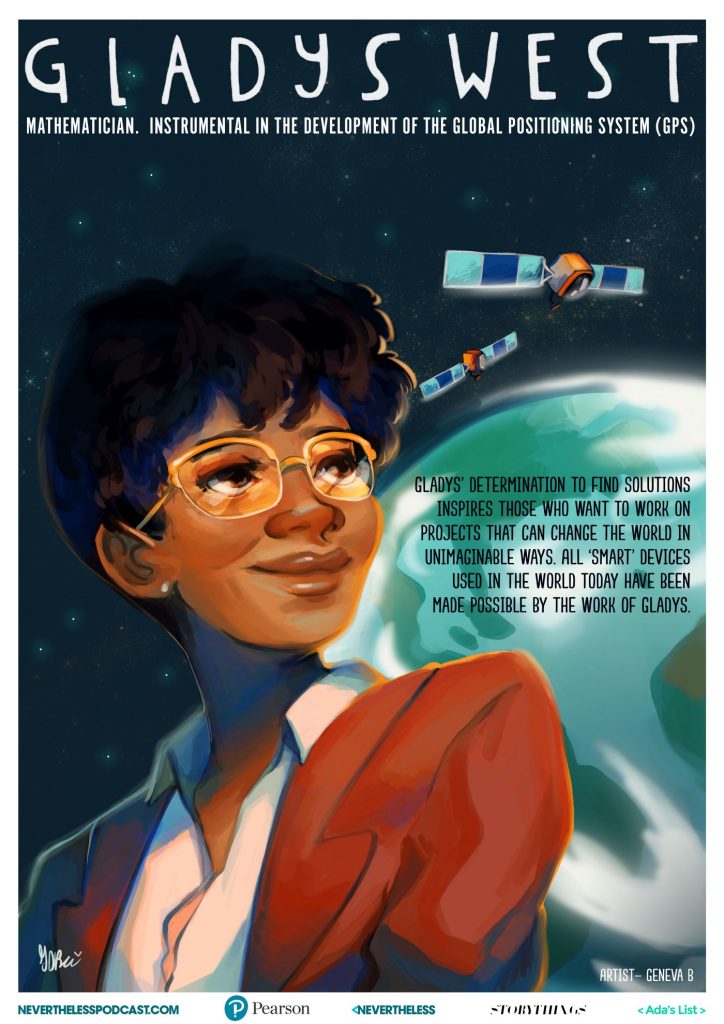

Part of the issue is related to the fact that STEM has a reputation as a traditionally male field. Science and maths are positioned as “boys subjects” by educators or family members, which can discourage young girls. This prejudice has been decreasing the last few years and is something that is increasingly countered by having more female role models for aspiring scientists. But this gendered prejudice also means that perceptions of male and female scientists are different. Even with the same qualifications and experience, women are often rated as less qualified than men with the same experience. Biases like these are deepseated and can only be dismantled gradually.

Another way of directly encouraging girls and women to pursue STEM fields, are initiatives like Hessen Technikum and Mentoring Hessen. The Hessen Technikum is designed to give women who are just finishing school the opportunity to get practical experience while doing a taster STEM course. Mentoring Hessen is an initiative meant to provide mentoring, training, and networking opportunities to women in STEM. Projects like these are a concrete method of providing pathways into STEM, as well as supporting and connecting women who are already studying and working in STEM jobs. It is a long road to getting women equally represented in STEM fields, but projects like these are helping to pave the way there.

Sources

Episode 44 – Ist der Frauenmangel in MINT von Stereotypen getrieben? – Datenaffaire

MINT-Herbstreport 2021: Mehr Frauen für MINT gewinnen – Herausforderungen von Dekarbonisierung, Digitalisierung und Demografie meistern – Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft (IW)

More Data Needed | Harvard Medical School

STEM Role Models Posters — In 7 Additional Languages | by Nevertheless | Nevertheless Podcast | Medium

Why aren’t airbags in cars also tested to take women’s breasts into account? – Innovation Origins